548 W 28 Street, Suite 634

New York, NY 10001

917-675-6884

Tuesday-Saturday, 12:00-6:00 pm

1241 ARTSPACE

Thursday, September 23, 2021, 6:00 PM — 8:00 PM

1241 Carpenter St, Philadelphia, PA 19147

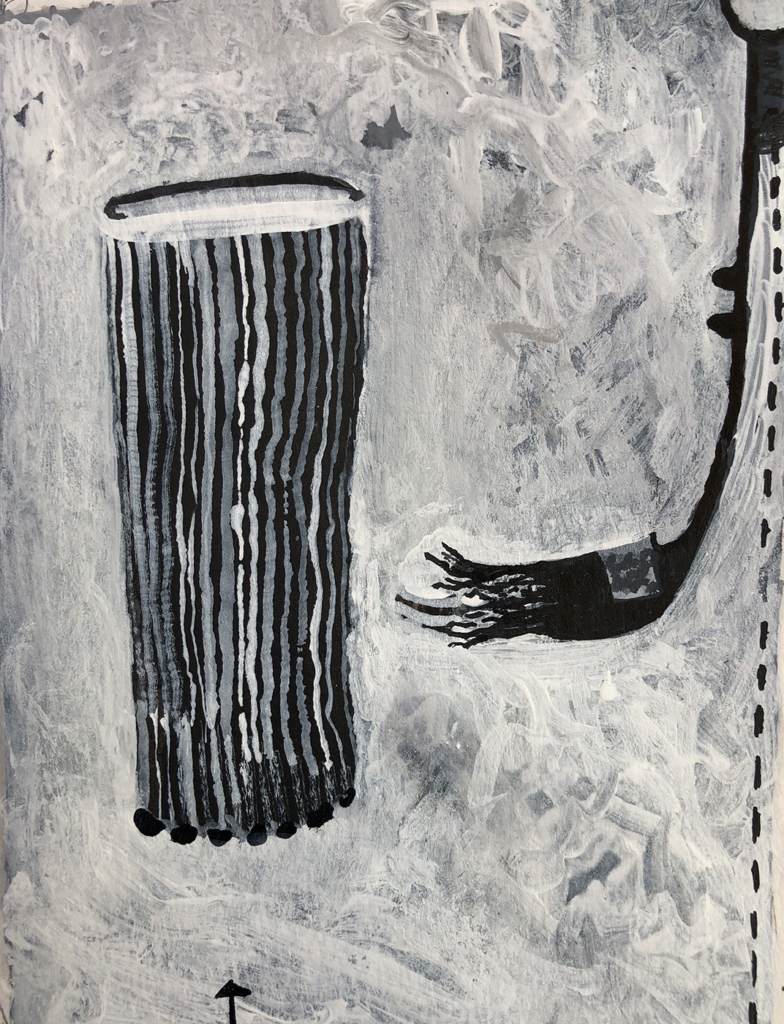

“Untitled”, from the Pandemic Sketchbook Series, 2021

As MOMA closes in on the final weeks of their exhibition: “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs” (October 12, 2014–February 10, 2015) my reflection wanders toward two important, and particularly key paintings that unlock a door to Matisse’s last decade of creativity. Both are in the Barnes Foundation in Philadlephia. In particular, the first painting that I recently visited was Matisse’s Le bonheur de vivre (1905–1906) which luxuriously resides in a new alcove.

Hanging directly across the open hall atrium from the Fauvist masterpiece is the second painting, the equally spectacular and renown mural known as The Dance, which is tucked away in three vaulted lunettes above the main gallery.

Dr. Barnes purchased the fabled Le bonheur de vivre directly out of the famous (or infamous) Salon of Gertrude Stein and in the case of the second canvas, Barnes specifically commissioned Matisse for the large mural and is the piece where Matisse vigorously began working with the paper technique.

It has also been argued by critics that Le bonheur de vivre is one of two paintings standing as a seminal pillar to the entrance of Twentieth Century Art. With the other being created by Pablo Picasso in direct reaction against the Matisse painting, which Picasso had seen at a momentous gathering of friends and cohorts at Ms. Steins. Picasso, as some postulate, returned to his studio with the determination of making an antithesis canvas to Le bonheur de vivre, and the result was Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon… originally titled The Brothel of Avignon).

According to Hilton Kramer, “[the cognoscenti] understood the Les Demoiselles was at once a response to Matisse’s Le bonheur de vivre”. Kramer goes on to say that Bonheur is not as well known because the painting was secluded in the Barnes Foundation with onerous viewing rules for over fifty years. The Barnes recently relocated to Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway a few blocks away from the Philadelphia Museum of Art and readjusted it’s operations

Currently Matisse’s Le bonheur de vivre or Joy of Life painting is not only being viewed by admirers, but observed by conservators as well, for the image is degrading, due to an oil binder with the cadmium sulfide-based yellow that is switching to a white or brown as it is exposed to carbon dioxide over time. But, Joy of Life is a key painting, it has everything that interested Matisse at the time and for what-was-to-come.

The center area of dancing women will appear throughout Matisse’s oeuvre, as in: MOMA’s oil sketch of Dance II purchased by John Quinn (which was another piece that came off the walls of Ms. Stein’s Salon), the Shchukin commission of Dance now hanging in the The Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg Russia, and ultimately the Barnes Foundation Mural which begins to turn the master’s eye to the technique of using paper as a means in-and-of-itself. The Bonheur piece exemplifies a color sensibility that continues throughout Matisse’s work, ending with the bright gouache pieces of paper cut-outs, it is also strangely reminiscent of Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. But, with Matisse’s painting, a matriarchal crowd and an Eros figure playing pipes is joyously celebrating, dancing to the end (not being ogled). In Le bonheur de vivre Matisse is ringing a bell for everything that seems to follow in his career as an artist.

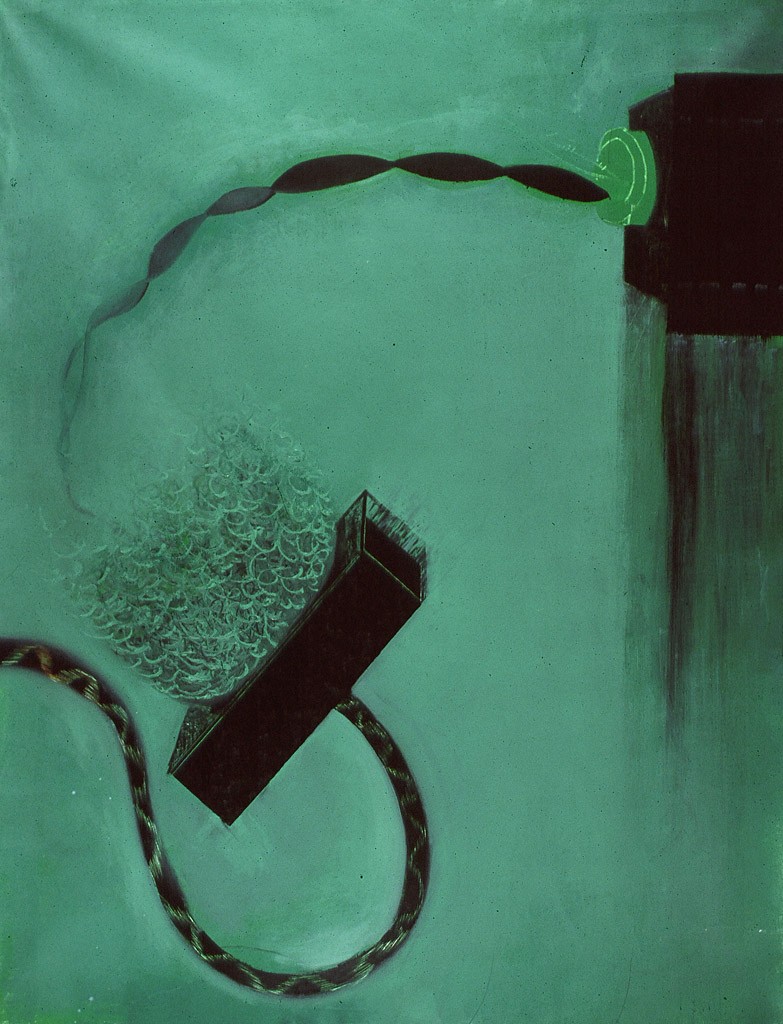

The Primary series was a distillation of the previously created material from the 1990’s and before. The 90’s paintings with elusive forms and freewheel senses were tremendously successful in exhibits, but I wanted to push the images with a voice that would be more singular. With that intent, using saturated color fields as background became the norm — in part as a technical device, because it upheld the concept of the back plane. However, since they were so expansive as canvases and were based on more-or-less pure color (hence the name “primaries”), there was a depth to the field that was visually arresting and that began its own conversation about figure and ground. Where was I going?

So many artists talk about the world around them by what they create and how everyday objects influence them, Claes Oldenburg for instance or Jeff Koons. Other artists like Clyfford Still seem to say that everything he painted came from within and had nothing to do with the outside world. Paul Klee, whom I’ve always admired if for nothing else than his ability to be exceptionally removed from the Art Star world of his time, created a strange and private universe. It’s always an interesting conversation: where are artists coming from? what are they saying (if anything)? and how or by what means are they practicing and employing their craft? Personally, I try to avoid dogma. But with Primaries, I came the closest to developing a rigid dogmatic system, by operating within set parameters of dark forms, saturated color, and little to no overlapping. Again, it was this pushing, finding, and achieving something that I felt which was driving me.

The paintings of Primaries were made while the canvas was pinned to the wall, which initially presented its own problems since I was looking for a particular type of surface that was smooth and even. I still work on the wall in this manner, but I’m more open to the texture and defects of the underlying surface. In fact, I welcome them. The rigid support permits a physicality of paint application and techniques (forceful scraping, rubbing, sgraffito, etc.) without damaging the surface of the canvas. The experience of approaching painting while the oil remains fluid provided the best and very challenging opportunity to create a picture; partially because as the form develops a visual memory builds, taking place very quickly as one tries to call forth an image –and as such, the act of paint manipulation becomes an integral dialogue of where to go, what to leave (and when a dynamic is achieved) when to stop.

Sometimes, especially in the work from 1996 to 2000, I did a large canvas in one day. Over time this way of working was exhausting, and I found some canvases would dry faster than expected from the day before. I liked where that particular painting was going. So I kept it, rolled it, and started another piece, always thinking I would go back to the dried canvases in a couple months, unroll them, and start into one or two. After years, they are like old friends coming back to roost, calling my name from the stacks, and popping back onto the wall, while I might be working on yet another set of paintings. Because this drying and rolling turned into a procedure of my working habit that I’ve embraced, I also have developed quite an “unfinished” inventory. Now, years later, I realize these rolled works have assisted in the process of how I see and what I’m currently doing.

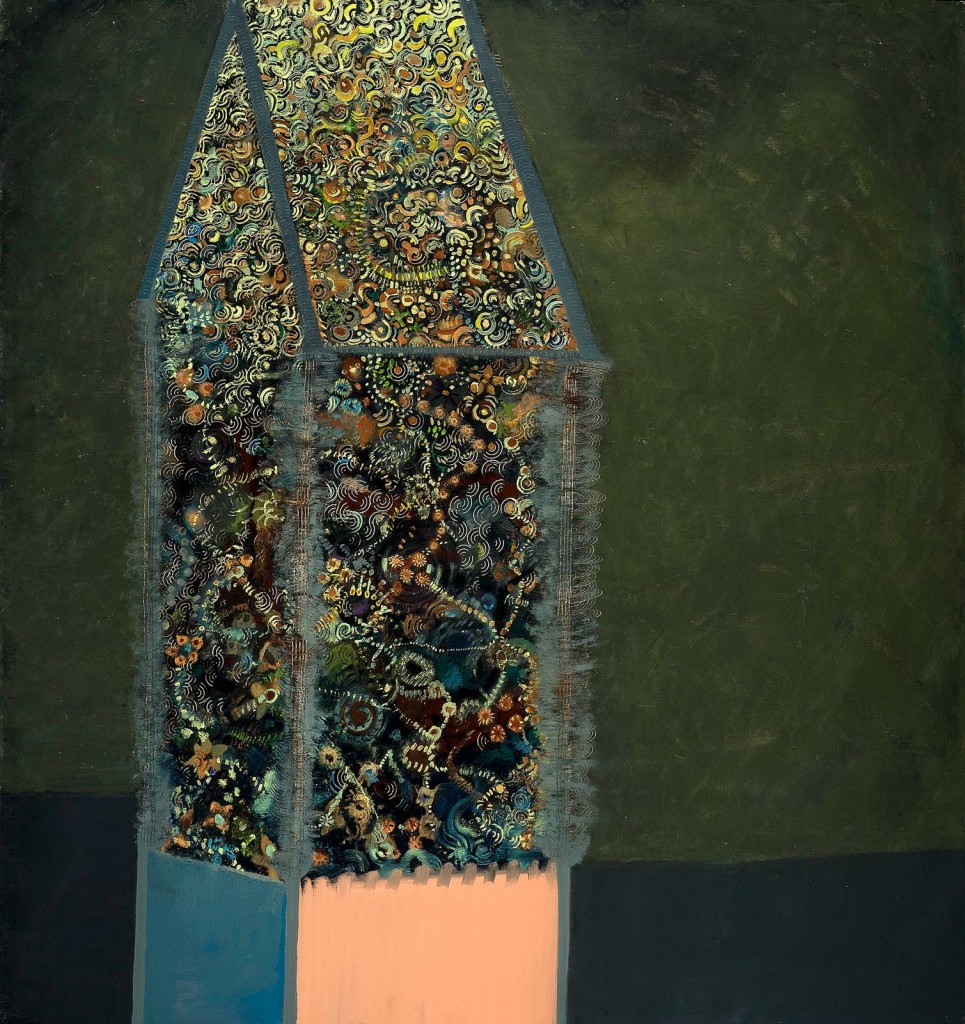

I came to the work I did about clouds, in part because I wanted to break away from some of the self-imposed restrictions in the previous works I titled Primaries. Even in my current work, many procedures remain from the Primaries, but I wanted to move on, and the subject of clouds seemed to free me and permit a sense of humor to enter the working mentality.

Joyce tells us that any object deeply contemplated can represent a window on the universe. Clouds are one of those earliest memories that provided amusement and meditation through their shape-shifting abilities. As a young boy, I would lay on a hillside and look at the different shapes they formed. I find myself drawn to the overhead expansive grandeur of clouds mixed with the luster of the sun. Clouds instill a tangible awe that permits me to reach towards a physical affirmation of life and an escape route from it at the same time. I speculate on the origins of these ephemeral forms, their destination, and their ethereal connections. Clouds, remain a source of wonder and mystery through their mutable presence.

I came to find out that meteorologically speaking most of the clouds depicted in my series were of a low and mid-level formation type. Other “specialty” clouds such as the Kelvin-Helmholtz (can you tell I began to learn a lot more about clouds than expected?) demonstrate the fantastic pattern that water vapor is capable of attaining. In appearance, clouds may be opaque or transparent, hard or soft edged, hair-like, towering, or in sheets, and they may signify fair weather, precipitation, or portend significant events. Consequently, they lend themselves to an array of artistic possibilities and meanings — something I began to think about and like very much, because Picasso was also able to make work that referenced work-a-day issues without being specific about them in a direct narrative fashion.

It appears to me that in all its manifold forms Western Art depicts a series of representations of the life around us in a visual format — at times recognizable, and at other times elusive. Because my images tend to come from a personal place, I am always in search of archetypal forms that can be manipulated with a sense of subtle resolve and meaning. The use of clouds in a narrative, pop-funk, painterly fashion may appear to break with other bodies of work previously created. But aside from the Cloud canvases being fun to make (humor was possibly more present than before) they became reference points like all my earlier work, serving as access guides into a painter’s world that is of my own conjecture and mythology.

Sometimes I touch (but anymore I’m often finding myself reaching for) a mystical chord by exploring highly personalized images that uncover ideal forms already embedded in the material. Clouds fit the bill.

Established in 1978, the Wind Challenge Exhibition Series is an annual juried competition that is committed to enriching and expanding people’s lives through art. Wind Challenge Exhibitions feature the work of exceptional artists living in the Philadelphia region.

Challenge 2 will include the work of Corliss Cavalieri, Jerry Kaba, and Sarah Peoples.

The Wind Challenge Exhibition Series is made possible with thanks to generous support from the Wind Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and through Fleisher members.

Since its inception, the series has introduced regional contemporary art from over three hundred artists to a broad audience and has helped emerging artists advance their professional careers. Past Wind Challenge artists include photographer Robert Asman and sculptor Syd Carpenter, both of whom were later awarded a Pew Fellowship in the Arts; beloved Fleisher teaching artist Charlotte Yudis; and brothers Billy and Stephen Dufala, winners of the 2009 West Prize. In 2011, a series of free-public programs led by the artists was introduced, designed to enhance the viewing experience for youth and adults.

Paintings and drawings 2009-2012 showcases Corliss Cavalieri’s work of the last three years. A continuation of his imaginative hide-and-seek forms, this body of work was inspired by Fabric-Row, the South Street Corridor neighborhood where the artist resides — a carnival of pattern, neon, and popular culture. The NOHO exhibition includes an array of marvelously idiosyncratic and somewhat wacky large paintings and small drawings completed in his Philadelphia studio as well as at artist residencies.

“I knew the more recent large works would be a perfect fit for our Chelsea space and am pleased that we were able to arrange this exhibition,” said Leon Yost, artistic director of NOHO Gallery, one of the oldest artist-run cooperatives in New York.

Fanciful imagery commingles with the vestiges of expressionist technique. The artist is pinning the work directly to the gallery walls, just as he would make them in the studio. By applying a canvas directly to the walls of his workspace, Cavalieri incorporates the bumps and offset surfaces of the rigid support into nuanced, textured multi-layers of thinly applied paint.

Corliss Cavalieri lives and works in Philadelphia. He has exhibited throughout the northeast, receiving his MFA from Tyler School of Art, and BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art. He has held residencies at the Vermont Studio Center, Virginia Center for the Arts, and Yaddo. Cavalieri is former Curator of the Philadelphia Civic Center Museum and past Gallery Director of the Paul Robeson Art Gallery Rutgers – Newark.